By Layli Foroudi. AUGUST 28 2020

Traditional methods that kept temperatures down are being relearnt amid intensifying heat waves

I cannot sleep inside during the summer in Tunis. My flat is on the top of a three-storey building in the centre of the Tunisian capital and it transforms into a furnace for the months of June, July and August. The walls emanate heat, which is then moved in circles by a fan that tries in vain to cool the room. Come nightfall, temperatures dip and a breeze returns, but the air inside remains suffocatingly thick and warm. I noticed that my neighbours had taken to sleeping outside on their patio, and so I followed suit and started sleeping on the roof terrace.

Relocating outside is a longstanding technique for sleeping comfortably in hot climates. My father told me that while growing up in Iran, he and his brothers used to move mattresses to the roof to sleep in the summer. This stopped when they moved house and got an air conditioner.

Though the air conditioner has now become a go-to solution for keeping cool, it is an ecological disaster. Buildings use more than half of the world’s electricity, mostly for temperature maintenance and ventilation, with air cooling accounting for nearly 20 per cent, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Last year, it was responsible for 1 gigatonne of CO2 emissions: ironically, technology built to cool is warming the globe.

When you walk in, you would say it is air-conditioned — the stone absorbs the heat and doesn’t let it into the house. Chiraz Mosbah

Air conditioning has fundamentally changed the work of an architect, says Alan Short, professor of architecture at Cambridge University and author of The Recovery of Natural Environments in Architecture. “Architects are no longer thinking about the environments in their buildings — the air-conditioning engineer does that.”

Climate change is making it increasingly urgent to revisit this neglected topic. Heatwaves are growing in number and intensity across the world. The Middle East reached record temperatures over 50C this summer and on August 17, Death Valley in California set the world record at 54.4C. Europe is also experiencing more heatwaves and its cities are being encased in heat bubbles: this month, the UK saw the longest stretch of high temperatures since records began in the 1960s, reaching 37.8C; last year, Paris recorded its hottest temperature ever at 42.6C.

The thick stone walls of the Medina in Tunis with wooden doors painted in blue and white © Alamy

Those who cannot afford AC are set to suffer the most, and those who can are aggravating the problem. The IEA predicts that energy demand for space cooling could more than triple by 2050, if no action is taken. Yet, Short says, “it is absolutely possible to make comfortable buildings in hot climates with little carbon consequence [but] architects generally pursue badly outdated, late-modern models”.

Traditionally, houses in Tunisia were built to minimise heat. Walls are made of thick stone and the central patio is partially covered with an iwan, providing shade and cooling the air outside the rooms, says Chiraz Mosbah, researcher at the Laboratory for Archaeology and Architecture in the Maghreb, whose own house in Tunis is built with 50cm stone walls. “When you walk in, you would say it is air-conditioned — the stone absorbs the heat and doesn’t let it into the house.” (The walls in my building, which Mosbah tells me was built between the 1960s and 1980s, are much thinner.)

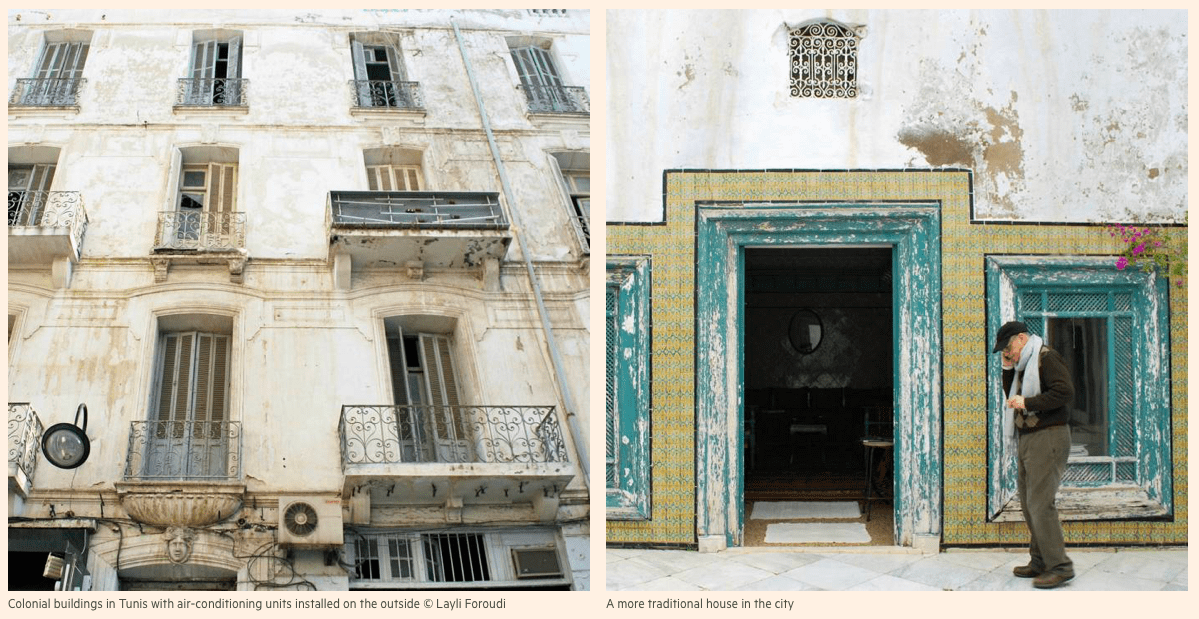

At the beginning of the colonial period in 1881, the new rulers dismissed traditional methods and started building houses in the European style and very quickly, in order to attract French people to live in Tunisia. “The colonial town was built with the ‘conqueror mindset’ and according to western principles,” says Mosbah: “It was not at all made for heat, [the buildings have] very big windows.” In contrast to the European-style avenues and houses, the labyrinthine streets of the medina were designed to limit heat and to preserve privacy. “[The French] exteriorised their wealth and opened their houses to the outside, but when we close the house we have less heat also.”

The glass tower is the most extreme expression of a house “open to the outside”, and most vulnerable to the sun’s rays. The now ubiquitous style took root in the US just after the second world war, with the construction of entirely glass buildings with steel frames. Structures from the 1950s, such as Lever House in New York, were then reproduced around the world regardless of climate, a shiny iteration of the modernist aesthetic known as the International Style. “The idea was to make identical looking buildings for everywhere in the world, and the idea of air conditioning is that you would make every interior the same: cool,” says Short.

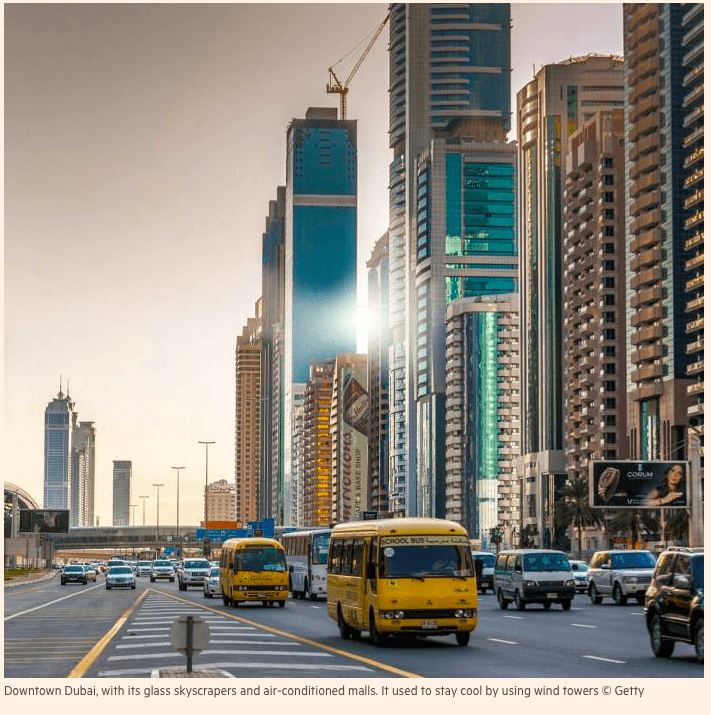

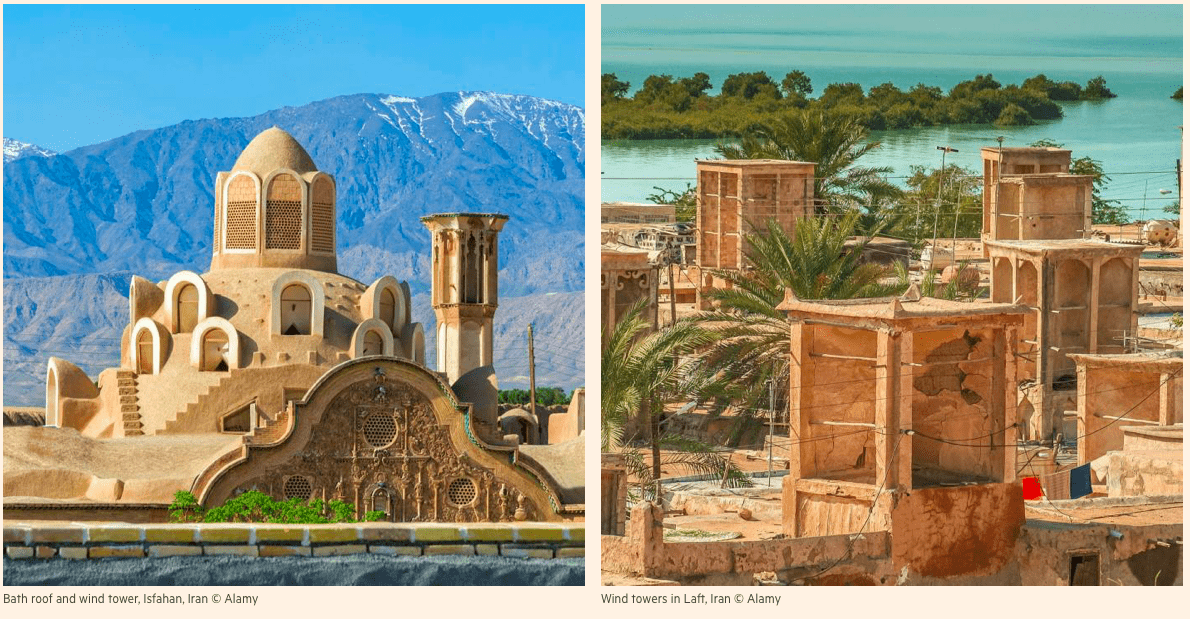

The city of Dubai is now known for its glass skyscrapers and air-conditioned malls but it used to stay cool using wind towers — square turrets on the top of a building that would channel air inside via openings on all four sides. These towers — which have been used in the Middle East since at least 1300 BCE — naturally conditioned the air in buildings by manipulating the wind. In Dubai, wind towers have been abandoned since the early 20th century — except as a nod to heritage on buildings, benches and ashtrays — but elsewhere architects are using them to eliminate the need for air conditioning.

We’ve tried to build back into the towers the advantages of these traditional houses in the Middle East. Alan Short

Short and his colleagues used wind catchers and stone in the design for the process building of Farsons Brewery in Malta — one of the earliest zero-carbon buildings — managing to drop the temperature 14C below the peak temperature outside. In China, they used wind tower-inspired methods to make air circulate in modern 25-storey buildings. “We’ve tried to build back into the towers the advantages of these traditional houses in the Middle East,” he says, adding that the coronavirus pandemic has underlined the need for natural ventilation in buildings to help flush viruses out of buildings. The same ancient technology was repurposed by ZEDfactory architects, who dotted the roof of their zero-carbon housing development in south London with multicoloured wind tubes in 2002.

For some architects, interest in the ecological innovations of vernacular architecture is coupled with renewed cultural emphasis on the local. “There is a dissatisfaction with the flat architectural language [of] the International Style — every city is becoming the same, and there is a reawakening of interest in the green movement,” says Lucio Frigo, founder of Materia Inc, a sustainable urban development company. “People are now saying: ‘let’s rebuild the connection with tradition’.”

In Kenitra, western Morocco, a new train station by Silvio d’Ascia Architecture and Omar Kobbité Architectes is cloaked with a mashrabiya lattice — an element of Islamic architecture that reduces temperatures by creating shade and natural air ventilation. “The objective was to reduce air conditioning as much as possible [and] give the building an identity that recalls traditional architecture,” says architect Omar Kobbité.

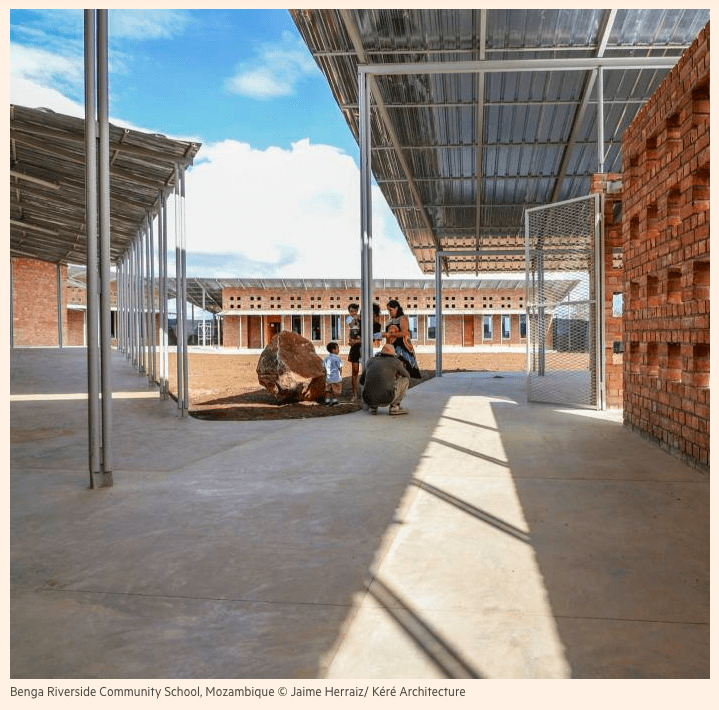

One of Frigo’s projects was a school in Mozambique with architect Francis Kéré, who designed an award-winning natural climatic primary school in his home town Gando, Burkina Faso, and the Serpentine Pavilion in London. The school is 12-15C cooler than outside thanks to clay firebricks, passive ventilation and a two-layer roof. But even so, Frigo says that “people complain a bit” about the heat and many clients still demand air conditioning, which conveys social status.

This is because we have been duped by the air-conditioning industry, says Susan Roaf, professor of Architectural Engineering at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh. “[They have] sold us the myth that you can only be comfortable between 20 and 26 degrees centigrade in order to sell us machines, but in reality humanity has been able to occupy a huge range of temperatures.” A house at 35C could be experienced as “comfortable”, depending on the person and location, she adds. It may take a cultural revolution to make air conditioning uncool.

Source: https://www.ft.com/content/839d4ccf-269f-44fe-914b-544644a4c819