Beating Urban Heat through Integrated City Action

Across the globe, cities are heating faster than the planet. Concrete, traffic and air conditioners trap warmth long after sunset, turning ordinary afternoons into health emergencies. The burden falls hardest on the Global South, where rapid urbanization, dark and impervious surfaces, and limited access to green space and cooling amplify exposure. According to the Handbook for Urban Heat Management in the Global South, by 2050 the number of urban poor exposed to dangerous heat could rise by 700 percent, with the most severe impacts expected in Africa and Asia.

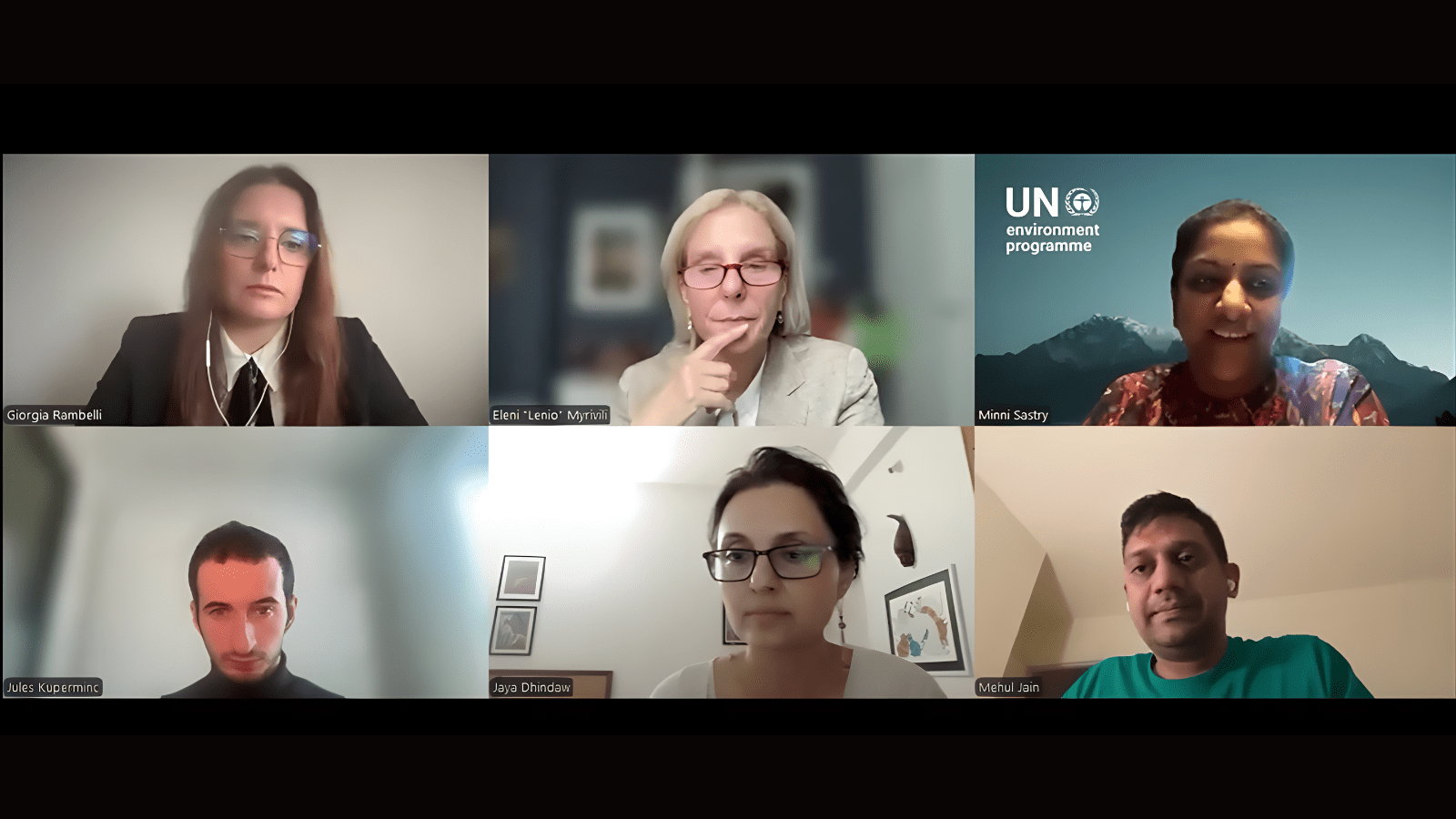

That escalating threat set the stage for the seventh Cool Talks webinar of the UNEP Cool Coalition series, which was held on 7 October 2025. Titled Integrated Adaptation for Urban Heat Challenges, the session examined how cities can move from recognising the dangers of extreme heat to delivering integrated, evidence-based solutions. It presented the Handbook for Urban Heat Management in the Global South, which was recently developed by the World Bank, UN-Habitat and UNEP, as a cornerstone reference for city leaders confronting rising temperatures.

Moderator Minni Sastry, Advisor on Extreme Heat and Sustainable Cooling at the UNEP Cool Coalition, opened the discussion by framing urban heat as one of the most acute and unevenly distributed climate risks. She described how densely built cities amplify heat through the urban heat island effect, where surfaces like asphalt and concrete trap and radiate warmth, often making city centres several degrees hotter than nearby rural areas. “Cities need evidence-based planning, integrated approaches and enabling policy environments,” she said, urging participants to see sustainable cooling as a cornerstone of adaptation. Her remarks set the tone for an hour focused on translating science and policy into practical solutions for urban resilience.

The first keynote grounded the conversation in evidence. Mehul Jain, Senior Disaster Risk Management Specialist for the World Bank introduced the Handbook for Urban Heat Management in the Global South as a guide born from field consultations in Uganda, India and Bangladesh, aimed at helping cities plan and act on heat risks. He outlined how it translates years of scattered research into clear, usable steps for city leaders, from identifying who is most at risk to turning plans into financed projects. The Handbook, he explained, is not theoretical but drawn from practice, built to support local governments with limited data and resources. “Heat impacts the most marginal sections of society first and hardest,” Jain emphasised, “so adaptation must begin with equity and scale through practical tools rather than abstract goals”.

Building on Jain’s call for evidence-based action, Dr Eleni (Lenio) Myrivili, Global Chief Heat Officer for UNEP and the Atlantic Council Climate Resilience Center, shifted the focus from guidance to delivery. Drawing on her experience leading city strategies and contributing to the Handbook, she argued that frameworks only matter if they drive implementation. That conviction underpins Beat the Heat, the new COP30 Presidency–UNEP implementation drive she is helping to shape. Designed to turn national pledges into local results, the initiative supports cities in conducting heat assessments, planning nature-based and passive cooling projects, and reforming procurement and building codes. It also creates channels for technical and financial partners to help cities move from plans to projects. Myrivili described the effort as a collective movement rather than a program, one meant to equip cities with the tools, training and support to act now. “We’re building the capacity and momentum for cities to protect their people in a hotter world,” she said.

The panel discussion that followed turned the spotlight on practical innovation, beginning with Jules Kuperminc, Product Manager at Google. Kuperminc described how Google is harnessing artificial intelligence and geospatial data to help cities see and manage heat more precisely. He detailed the company’s expanding toolkit, which includes the Tree Canopy platform that maps shade coverage to guide urban forestry plans, and Cool Roofs that identifies reflective surfaces able to lower building and neighbourhood temperatures. Google’s latest Temperature Effect Modeling tool, he explained, goes a step further by letting cities test different cooling scenarios to estimate how each choice would affect local temperatures. “Cities need actionable insights, not just data,” noted Kuperminc, as he went on to explain that partnerships with US cities like Stockton and Phoenix have already turned model results into new ordinances and investment plans. Google is now adapting these tools for Ahmedabad, India, to ensure that cities in the Global South can access the same level of decision-ready information to guide their resilience strategies.

In India, that data is beginning to meet policy. Jaya Dhindaw, Executive Director of the Cities Program at WRI India, explained that true progress comes when evidence and governance align. She noted that cities like Mumbai and Bengaluru have learned to embed cooling measures, such as tree planting, wetland restoration and shaded public spaces, within broader development plans instead of treating heat as an isolated challenge. By integrating heat resilience into programs for water, housing and mobility, these cities are achieving multiple gains at once, from better health outcomes to lower infrastructure costs. “When cities stop treating heat as a standalone issue and more as a lived reality, solutions multiply,” she said, stressing that success depends on coordination, sustained finance and strong local capacity rather than one-off projects.

The discussion turned global with Giorgia Rambelli, Director of the Urban Transitions Mission at the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy, shedding a light on how city networks are helping local governments learn from one another and scale adaptation efforts across regions. She shared examples from Kisumu County in Kenya, where cooling goals are embedded into law and linked with renewable energy targets; Greater Manchester in the United Kingdom, which is partnering with the private sector to expand nature-based cooling and green jobs; and Belo Horizonte in Brazil, where a digital twin developed with the Singapore-ETH Centre is mapping heat exposure and social vulnerability to guide local action. Rambelli also highlighted the growing political and financial momentum behind sustainable cooling through the Global Cooling Pledge, the first collective global commitment to cut cooling-related emissions by 68 percent by 2050, which now counts more than 70 country signatories and 80 non-state supporters. “When cities learn from each other, they create the leverage national governments need to act,” she remarked.

The Q&A focused how cities can finance, coordinate and sustain heat adaptation. Participants discussed ways to integrate heat resilience into national housing and urban programs, exploring financial instruments that move cities from plans to implementation. Questions were raised about reducing heat in arid regions like Pakistan, prompting exchanges on passive cooling design, energy-efficient technologies and the revival of traditional architectural methods. The role of governance surfaced repeatedly, with several speakers noting that adaptation succeeds when ministries, municipalities and local communities plan together. The discussion closed with a shared recognition that while technology and finance matter, long-term resilience will depend on building institutions that treat heat management as a permanent urban priority.

As the session closed, Minni Sastry thanked the speakers and participants, noting that the conversation had traced a full arc from the science of urban heat to the tools, finance and cooperation needed to confront it. The consensus was clear: managing extreme heat is no longer a seasonal or technical issue but a central test of climate resilience and urban equity. The Handbook for Urban Heat Management in the Global South and the Beat the Heat Implementation Drive now offer cities both the guidance and the platform to act for people and the planet.

More on the event, including speaker presentations and the recording here.